-

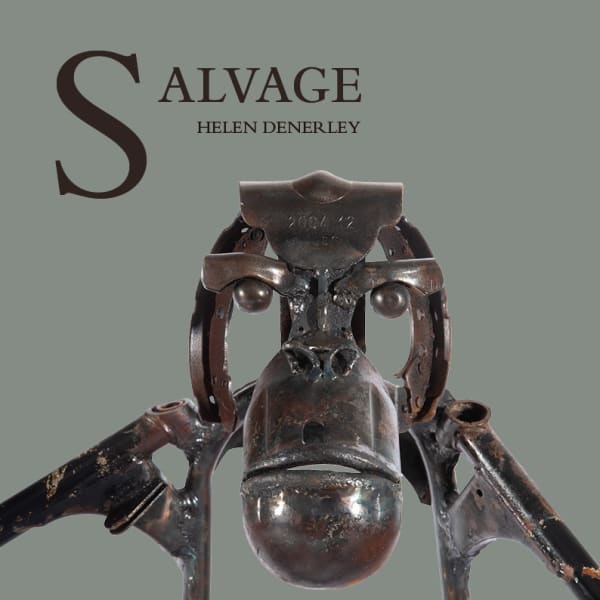

Helen Denerley Giant Spider 2023 (combine harvester dividers, gas guns, tanks and barbeque lid3.3m high)

Helen Denerley Giant Spider 2023 (combine harvester dividers, gas guns, tanks and barbeque lid3.3m high) -

Salvage -Helen Denerley in conversation with Georgina Coburn

Putting these passions together, metal and nature in all its guises is what my life is and so it is a natural result that these two elements will combine intuitively to become sculpture.

Helen Denerley

GC: In taking scrap metal and transforming it into living creatures, you’ve distilled a unique vocabulary of metal parts- not just in line and form, but intention. How do you see this library of knowledge, drawn from industry and nature?

HD: I have always been drawn to metal as a medium, steel in particular, how the colours change with heat and oxidise with time, how it can be melted, moved and joined. The process of welding is something which I can lose myself in, molten metal flowing, green, through the welding glass. My scrap pile is my library and I know where everything is. It is arranged according to shape, buckets of eyeballs, piles of feathers, shelves full of possibilities. New scrap is filed away and memorised so that when I need a particular part, I can find it easily. Sometimes it works the other way round and the starting point will be me, standing in the scrap pile looking around and being drawn to an interesting shape with the possibility of what it might become. The first wolf I made was because I picked up a heavy rusty old brake calliper and saw a wolf’s forehead. Living as I do, remotely in the Eastern Highlands, I am surrounded by wildlife, as well as farm animals and the occasional pet. I have always loved to be a part of this landscape and the life it supports. The birds punctuate the year with their migrations, and I work with the seasons like any other mammal as the year unfolds. Spending a lot of time outside I am often alerted to a passing raptor by its call and so the awareness of the natural world is key in my life. Putting these passions together, metal and nature in all its guises is what my life is and so it is a natural result that these two elements will combine intuitively to become sculpture. It is less about intention and more just going with what feels right and using a lifetime of learnt skills to make it happen.

GC: Clearly the spark of material brings a lot of joy, to you as an artist, but also to your audience in seeing the spirit of living things emerge from discarded scrap. Can you tell us how your process has evolved over your 45+ year career? Has the spark of ignition changed or remained constant?

HD: When I started out as a sculptor, I didn’t have a library of scrap or a purpose built workshop and far fewer tools and equipment. I used only quarter inch rounded steel rod which could be bent in a vice and joined with an electric arc welder. I was always inspired by the line drawings of Picasso, David Hockney and in particular Alexander Calder. I used metal rod to create three dimensional drawings, lines in space. Perhaps that is the most difficult challenge as a sculptor and one to which I return often, whether with a steel rod or any linear piece of metal. When I started to use scrap I was delighted to find that my control over the outcome started to diminish and the pieces would suggest the next move. I still refer to an image in my head or a charcoal drawing on the wall, but the scrap will present an unintentional negative space and I work with that to create positive space. The gaps in the sculpture are filled in the imagination of the viewer and air becomes muscle and flesh. I am not concerned about what the piece of scrap was in its former life as it is selected for its shape, weight and texture, but just sometimes, it will bring with it a story which further enriches the piece. First and foremost, it is the success as a sculpture which is most important and if it is an animal, it needs to capture the essence of the creature, but the secondary interest in the parts used is an extra dimension and one which continues to surprise and enthral me. For as long as I keep using scrap, I am not in danger of becoming repetitive or bored with the process. A new arrival in the scrap pile will trigger the excitement of new possibilities and keeps my enthusiasm alive.

GC: You’ve described your latest solo exhibition Salvage as a milestone. Can you describe the core elements or energies in this new body of work and what is essential to you personally in making sculpture?

HD: The lockdown years provided a pause for many artists, with deadlines extended and a greater chance to reflect and reassess. For me, the time was spent re-engaging with my surroundings, cutting broom, planting trees and hearing birds more clearly in the unnatural quiet of the time. I allowed myself to look, feel and listen with renewed intensity. I have always had a strong sense of place and it was joyous to feel completely immersed in it. I became aware of a particular song thrush and could hear it above the others. With the help of a friend, I made a bench from whisky barrel staves and set an engraved copper thrush in the bung hole. There I could sit and listen to the bird with a coffee or a dram in hand. I then made a song thrush in scrap and wrote a short poem in its honour. After lockdown, Jenny Sturgeon, a song writing friend phoned to compare notes on our lockdowns. Inspired by my story, she went on to write and record a beautiful song about the song thrush called Salvage. That has become the title of this show.The power of nature and collaboration at its best. I made a present for a new young restauranteur, a peacock, using bits and pieces entirely related to kitchens and cooking. It brought back the fun and freedom of scrap metal sculpture from the early days. This exhibition brings back that joy, using scrap in a freer way which is fun and thought provoking. All my years of drawing and meticulous observation have finally combined with that freedom. I couldn’t do it without the experience gained, learning how to push the form, the material and myself to the limit. The making of art is not separate from being an artist. My connection with nature and my way of life are the art and as a committed artist, through the joy of scrap metal and the skills I have accumulated, I am now in a wonderful position to share that joy.

GC: From tiny bees, butterflies, and enormous spiders to birds of prey and orangutang, your metal constructions and drawings are beautifully observed. Can you describe the process of recognition of other living things in your practice?

HD: I have never differentiated between being human and being a part of the natural world. As mammals we are more connected to the forces of nature than we might think and watching how mammals behave can be a telling insight into some of our own behaviour. Observation is key to drawing and creating but it is also key to understanding ourselves and others. If we paid more attention to our place in the natural world, perhaps we could empathise more both with it and each other. How we observe ourselves is a question that many of us never ask but in the setting of a museum, particularly an anthropological one, it would be hard to ignore. In Salvage, I have created the atmosphere of a museum, there are specimen boxes, a hanging skeleton, Orangutans sit at the corners of the room, observing each other and us, asking us questions. As a student in the seventies our sculpture class went on an expedition to London and for many of us that was our first experience of grand museums and galleries. I remember clearly how overwhelmed I was when entering the Natural History Museum, the carved pillars depicting animals and birds, an enormous skeleton of a dinosaur, a blue whale hanging. Room after room of glass boxes with stuffed animals and remnants of past human life. But the thing which stands out most in my memory, was a small room with a specimen box full of brightly coloured beetles. Metallic coloured wing covers and simple bold shapes, that was the moment when I knew which medium most excited me and there began my long love affair with metal. Years later I visited the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, a darkened room stuffed full of artifacts relating to human existence. I loved the feeling of discovery, opening drawers to reveal trays full of tiny artefacts individually labelled and archived. In Salvage I have intentionally created a tension between the viewer and the work, the questions are quietly there.

GC: Your latest exhibition features birds and animals, but also works which are more experimental and architectural, like the Infinity Column. There’s an elegant, rhythmic quality to the forms in this work which feels almost totemic. Can you tell us about the impetus behind this work?

HD: I see this exhibition as a retrospective of ideas and an opportunity to revisit some of the experiences which have inspired me over the last forty-six years as a sculptor. As a new student at Gray’s School of art in the seventies, I came across an image of Brancusi’s endless column. I remember being fascinated at how something so abstract and simple in form could be so inspiring. Since then, I have visited cathedrals and felt the same awe. Looking up empowers us to feel positive and hopeful, emotions essential in life. For many years I found good reasons not to use a pile of old conical fire extinguishers which have lain rusting under my now sprawling elderflower tree. I must have been keeping them for some greater purpose. Now is the time to make my endless column. The addition of the water tanks from inside oil boilers adds another shape and brings with it the questions around our use of energy and the scarce resources of the planet.

GC: How would you describe the exhibition as a whole and how do you see your role as an artist?

HD: Salvage is a collection of sculptures inspired by a lifetime of observation combined with the joy of the natural world and the love of scrap metal. In this exhibition I have created a spider, outside the building, large enough to walk through and with some very recognisable scrap. There are also tiny insects inside the gallery. Known mostly as a sculptor of animals, I have enjoyed the freedom to play with abstract form. I have created several chess sets for the exhibition using keys, spark plugs, golf clubs and simplest of all, found objects, beautiful in their own right. I hope the exhibition inspires those who see it and helps them relate to themselves, the natural world and those around them. As artists we can only encourage, inspire and influence through making our work with integrity and honesty.

-

-

-

HELEN DENERLEY | Salvage

a solo exhibition of new work by Helen Denerley 5 - 31 August 2023Salvage has come together with the sort of great leaps only an artist with a lifetime sculpting experience can conjure. It is in many ways Helen Denerley’s Everest, a peak,... -

Helen Denerley

HELEN DENERLEY is one of the UK’s leading wildlife artists and is best known for her scrap metal animals. She has had many major exhibitions (including four solo shows at... -

Catalogue

Salvage | new work by Helen Denerley catalogue July 28, 2023We are very pleased to share with you a publication printed to celebrate Helen Denerley's fifth solo exhibition in Kilmorack Gallery this August (2023.) We have called this exhibition 'Salvage'...

-

Salvage | HELEN DENERLEY in conversation: Sculptor Helen Denerley in conversation with Georgina Coburn

Past viewing_room