As a freelance writer and art historian I’ve always been fascinated by the unseen in Art. The power of handmade objects to reach within us, beyond our own time and place, originates in an essential process of transformation, experienced through the mind, heart and hand. This authenticity will always be felt and intuitively understood by an audience. We may not be able to put it into words, but we all know a living work of art when we experience it. What initially drew me to Steve Dilworth’s work was the living presence of his objects and the pure intent of making “real things”.

Three years ago, I began work on the artist’s biography. In the first stage of the process I documented his work from the 1970s to the present and then interviewed family, colleagues, public custodians and private collectors of his objects. The relationships people from all walks of life have with his art are revelatory.

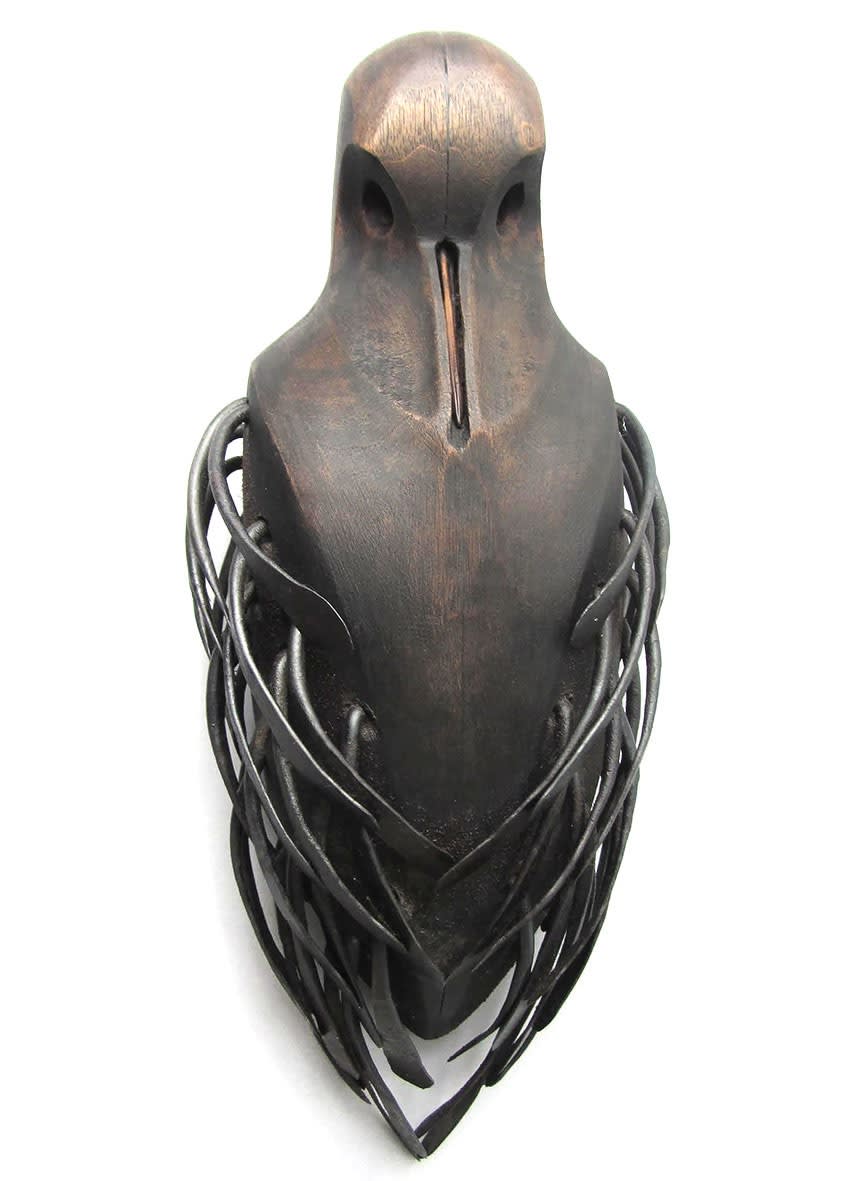

For over 35 years Steve Dilworth has been consistently breaking new ground as one the UK’s most visionary artists. His remarkable work in stone, wood, bronze and once living material is a constant source of surprise and discovery. Dilworth’s approach and unique fusion of raw materials is unlike any other artist I know, contemporary or historical. Although he is often described as a sculptor, traditional modes of representation, symbolism or memorialisation have never defined his practice. It’s true that Dilworth’s objects are aesthetically beautiful and crafted with devotional care, however his global significance isn’t rooted in the visual. What his art reconnects us with goes far deeper than what can be seen on the surface.

Dilworth’s works are not passive art objects, placed on a plinth or mantlepiece and admired from afar. They are held close, passed between generations, used as touchstones of contemplation, comfort and confrontation with all that we love and fear in life.

What strikes people immediately, as Dilworth himself was struck, sinking his hands into the earth forming balls of clay as a child, is the eternally tacit, how we make sense of the world and of ourselves through creative process. Humanity is a tribe hardwired to seek meaning by making. What many people experience in Dilworth’s art reawakens what first drove our prehistoric ancestors to make cave paintings and hand-held objects. His work taps into the collective unconscious and genetic memory in unexpected ways.

Hold one of his throwing objects in stone or wood in your hands and you feel an uncanny balance of form and energy, connecting the core of the body to all things. His art isn’t about ego, but the vital charge of forces greater than ourselves in nature connected to the human nervous system. It’s the inner knowing Dilworth encountered running his hands along a Henry Moore sculpture as a child while no one was looking.

Steve Dilworth Woodcock

Dilworth’s objects are conceived and crafted from the inside out, with the raw power of material as the vital spark of ignition. What is most valuable or sacred is held inside the object, unseen, yet we sense it is there in its completeness. Like indigenous art from around the world, there is no separation between the physical and metaphysical. Dilworth’s practice excludes nothing, from ritual belief to particle physics. Intense curiosity, experimentation and play have always been an essential part of his process. The artist’s home on the Isle of Harris in the Outer Hebrides is a highly sculpted environment where our relativity to Nature and time become clear. It is the perfect imaginative ground for Dilworth’s sublime and evolutionary work.

Georgina Coburn